The law on damages regulates the conditions under which the injured party can demand compensation from the injuring party for damage caused by the latter – thus, damages are primarily concerned with the question of bearing the damage. In addition to this (primary) compensatory function, the law on damages also pursues a preventive purpose. Thus, the threat of an obligation to compensate is intended to encourage conduct in conformity with due care in order to avoid damage.

In most cases, the liability for damages is a so-called fault-based liability – the essential prerequisite for the occurrence of the liability for damages is, on the one hand, the unlawfulness and, on the other hand, the fault of the injuring party (for the exact prerequisites, see below). Such fault-based liability may arise either due to a breach of contractual obligations or due to the commission of a tort.

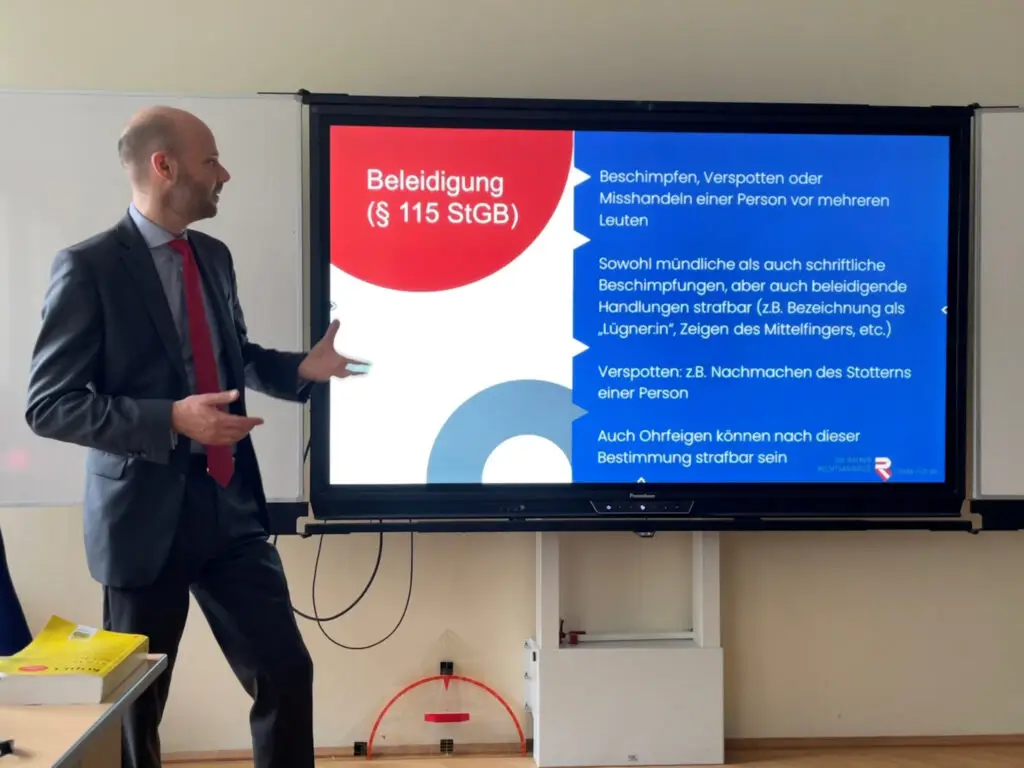

Example: A hits B in the face during a scuffle, whereupon the latter suffers a broken nose. B then has to go to hospital and suffers severe pain.

Example: A owes B the purchase price of EUR 3,500 under a purchase agreement, but fails to pay it on time.

In addition, however, there are also constellations in which fault is not taken into account, but a duty to compensate exists solely on the basis of the danger associated with an activity – this is referred to as strict liability. The purpose of strict liability is that someone who uses an intrinsically dangerous object should compensate for the resulting damage.

Example: A loses control of his car while driving, skids and collides with B’s car. B is slightly injured and his car suffers a total loss.

Another possibility of justifying a claim for damages is liability for interference, although this is the rarest ground for attribution. The liability for interference enables the compensation of damage which has arisen due to a permitted activity. Permitted activity means, for example, justifiable necessity.

Example: A hiker gets into avalanche danger during the ascent and, in order to save himself, breaks into a nearby hut. In this case, he is justified, but must pay compensation for the disadvantage incurred.